Cybersecurity Labeling for Medical Devices

1.0 Purpose

This guide helps manufacturers understand and implement cybersecurity labeling that complies with the FDA’s 2025 Premarket Cybersecurity Guidance (Section VI.A.) and aligns with IEC 81001-5-1:2021 (Clause 5.8 and Annex E). Cybersecurity labeling connects design intent to real-world device use. It communicates to clinicians, IT administrators, and healthcare delivery organizations how to install, configure, maintain, and retire a device securely. The goal of this guide is to make labeling expectations clear, actionable, and accessible so that teams can produce labeling that supports both compliance and patient safety without unnecessary complexity.

2.0 Introduction

Cybersecurity labeling is required for every medical device containing software or network capability. It bridges engineering, regulatory, and communication disciplines, converting technical design documentation into usable guidance for end users. Section VI.A. of the FDA guidance defines fourteen (14) elements that labeling must include, plus the optional MDS2 Form. These requirements complement IEC 81001-5-1, which calls for accompanying documentation such as:

Secure operation and account-management guidelines;

Security options and configuration guidance;

Information on residual risks; and

Instructions for decommissioning and data removal.

Cybersecurity labeling is therefore both a regulatory artifact and a safety control. It is part of the Secure Product Development Framework (SPDF) and the Total Product Life-Cycle (TPLC) process described in SEC-GUIDE-07.

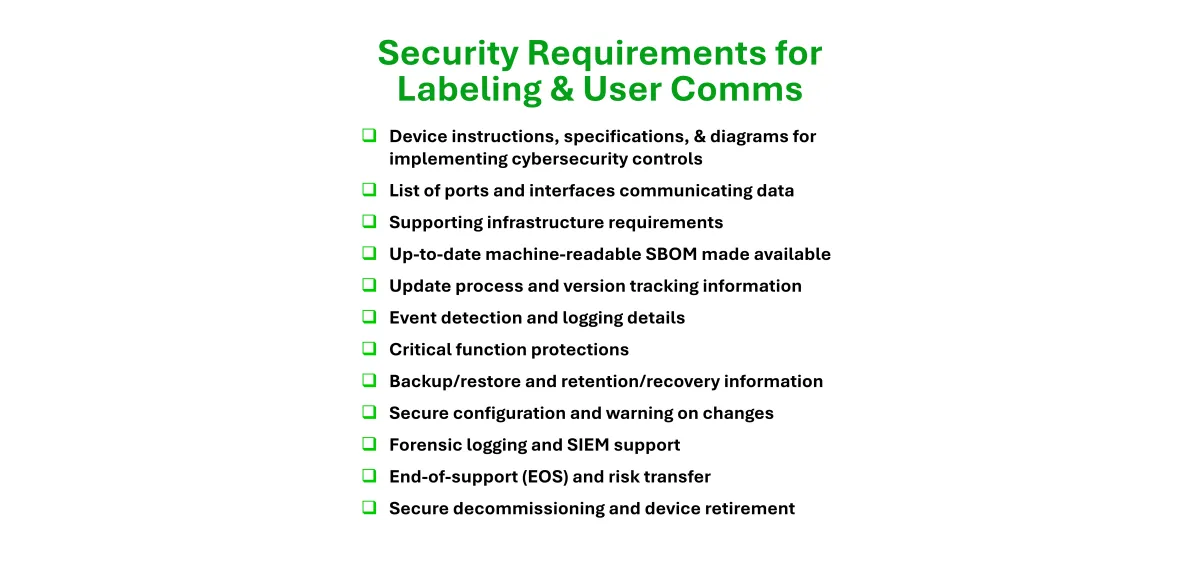

3.0 FDA’s 14 Cybersecurity Labeling Requirements

Each element below includes the FDA’s expectation, a plain-language interpretation, and Velentium Medical’s practical recommendations per Section VI.A. of the FDA Premarket Guidance.

3.1 Device Instructions and Product Specifications

Provide clear instructions for secure setup, installation, and operation, including any hardware or software specifications needed for safe use. Example: The IFU details installation steps, credential creation, and safe startup checks before clinical use.

3.2 Diagrams or Descriptions of System Architecture

Provide an overview of the device’s components, data flows, and boundaries of trust. Example: A labeled diagram shows the implant, programmer, cloud gateway, and associated trust boundaries.

3.3 List of Network Ports and Interfaces

List all physical and logical interfaces, the purpose of each, and which are enabled by default must be listed clearly in the labeling. Example: Labeling lists USB, Ethernet, and WiFi interfaces with the recommended information and notes that diagnostic ports are disabled in production firmware.

3.4 Supporting Infrastructure Requirements

Specify environmental and infrastructure requirements needed to maintain security. Example: Labeling notes that the device must operate on a segmented network behind a firewall and be integrated into the hospital’s Active Directory for authentication.

3.5 Machine-Readable SBOM Available to Users

Provide or reference a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) that lists all software components. Example: The SBOM is hosted on the manufacturer’s portal and updated with each software release; this is not the only way to provide an SBOM to users.

3.6 Authorized Update Process and Version Control

Describe how software and firmware updates and security patches are distributed, authenticated, and tracked. Labeling should clarify how the manufacturer delivers both routine updates (feature or performance enhancements) and patches (targeted corrections for known vulnerabilities). Example: The manual outlines a digitally signed, encrypted update and patch process verified during installation, with automatic version checks and logging of completed updates.

Tips:

Include version numbering and rollback prevention steps.

Explain how users verify successful installation and how the system confirms patch integrity.

State how users will be notified of new updates, emergency patches, or vulnerability advisories (e.g., through a secure portal, email alerts, or in-app notifications).

Identify who is authorized to perform updates and patches.

Reference the manufacturer’s coordinated vulnerability disclosure (CVD) process for reporting or receiving vulnerability information.

3.7 Event Detection and Response to Anomalies

Describe how the device detects, logs, and communicates anomalous or suspicious activity. Example: The IFU explains that repeated failed login attempts trigger a temporary lockout and generate an audit log.

Include instructions for reporting suspected security incidents or vulnerabilities to the manufacturer’s designated intake channel as part of the coordinated vulnerability disclosure process.

3.8 Features that Protect Critical Functionality

Identify the device features designed to preserve safe and essential performance during a cybersecurity event. Example: If network communication fails, therapy delivery continues in a default safe mode.

3.9 Backup and Restore Procedures

Provide instructions for securely backing up configuration and patient data and restoring it when needed. Example: Administrators can export encrypted configuration backups to verified storage media and restore using authenticated credentials.

3.10 Retention and Recovery by Authenticated Users

Explain how authenticated users can recover configurations and resume operation following an outage or failure. Example: After power loss, an authenticated user logs in and selects “Recover Settings from Secure Backup.”

3.11 Secure Default Configuration and Risk Warnings

State the device’s secure default settings and describe risks if they are changed. Example: Default network mode is “secure-only.” If the user enables “open network,” labeling warns of reduced protection.

3.12 Forensic Logging and SIEM Compatibility

Describe the device’s forensic logging capabilities and compatibility with enterprise security monitoring systems. Example: The manual specifies syslog format and instructions for forwarding logs to a hospital’s SIEM system.

3.13 End-of-Support (EOS) and Risk Transfer Process

Communicate how long the device will receive cybersecurity updates and how risk transfers after support ends. Example: The labeling states that security updates are guaranteed for 7 years, after which the device should be replaced or isolated.

3.14 Secure Decommissioning and Sanitization

Provide instructions for secure removal of devices from service and sanitization of data. Example: The IFU describes how to wipe stored data, revoke keys, and verify successful sanitization before disposal or resale.

3.15 MDS2 Form (Optional but recommended)

Provide the NEMA Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security (MDS2) to summarize device cybersecurity features and security controls in a standard, comparable format. Example: The MDS2 Form is provided as a downloadable PDF alongside the IFU and SBOM.

4.0 Integrating Labeling into Design and Risk Management

Cybersecurity labeling requirements should be identified early in the design process (SEC-GUIDE-10). For each control derived during threat modeling, ask:

Does this control require user configuration or awareness?

If yes, what labeling content communicates that responsibility?

Labeling content related to software updates, patching, and vulnerability communication should be identified early in the Secure Product Development Framework (SPDF). As part of threat modeling and cybersecurity risk assessment, determine:

Which risks will require labeling statements or user actions (e.g., applying patches).

How vulnerability intake and disclosure information will be conveyed to users.

How labeling will align with postmarket monitoring and coordinated disclosure processes described in the manufacturer’s cybersecurity management plan.

5.0 Best Practices for Clear Cybersecurity Labeling

Be transparent about patching and vulnerability management: clearly communicate where users can find update notices, vulnerability advisories, and instructions for reporting potential issues.

6.0 Next Steps

Cybersecurity labeling is both a compliance requirement and an opportunity to build trust. When manufacturers communicate security transparently, users are empowered to maintain protection throughout the product’s life. Velentium Medical helps manufacturers create labeling that meets regulatory expectations and speaks clearly to end users. Learn more at www.VelentiumMedical.com/Cybersecurity.

7.0 References and Resources

Velentium Medical SEC-GUIDE-00 - Navigating Cybersecurity during FDA eSTAR Submissions

Velentium Medical SEC-GUIDE-07 - Total Product Life-Cycle Security

Velentium Medical SEC-GUIDE-08 - Security Requirements and Controls

Velentium Medical SEC-GUIDE-09 - Cryptographic Assurance Levels (VEL-CAL)

Velentium Medical SEC-GUIDE-10 - Design-Time Risk Management for Medical Devices

FDA Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions (2025)

IEC 81001-5-1:2021 – Health Software and Health IT Systems Safety, Effectiveness and Security – Part 5-1: Security Activities in the Product Lifecycle

AAMI/ANSI SW96:2023 – Security Risk Management for Device Manufacturers

ANSI/NEMA HN 1-2019 Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security (MDS2) Form (https://www.nema.org/standards/view/manufacturer-disclosure-statement-for-medical-device-security).

Download SEC-GUIDE-11 Cybersecurity Labeling for Medical Devices in PDF Format

An example of cybersecurity content for a fictional medical device system is available in the PDF version of this guide.